In May 2018, the European Union enacted the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the toughest personal data privacy law in the world. Under the GDPR, EU regulatory bodies have levied several multimillion Euro fines, and other governments have proposed or passed similar legislation, using the GDPR as a template. However, in the two years since it was passed, there has been little consensus among politicians and pundits about the net effects of the GDPR for EU consumers and markets.

A new paper from T. Tony Ke (Chinese University of Hong Kong Business School) and K. Sudhir (Yale School of Management) investigates the long-term effects of the legislation, disentangling the dynamics of the personal data economy and the market implications of the regulation. In this post, we’ll provide context on the GDPR and cover the highlights of the paper’s analysis. We’ll also discuss some of the features of the model which might allow it to serve as a template for analyzing other privacy regulation regimes.

GDPR: a new era of data privacy regulation

After it was passed in April 2016, every organization dealing with personal data of people in the European Union — from tech giants to parent-teacher organizations — faced new responsibilities. The law established three critical privacy rights:

- Explicit consent. Firms must ask consumers to opt in to data collection and use.

- Erasure. Consumers must be able to purge their data from firm records.

- Portability. Consumers must be able to move their data to competitor firms.

Besides mandating privacy rights, the GDPR expanded previous privacy legislation in the EU to include protection of personal data like the profiles that companies create of consumers based on their Internet history as well as IP addresses and other information that can uniquely identify consumers. The law also requires that, after a data breach, firms notify a regulatory body and affected individuals within three days of the breach.

Infographic published by the European Commission promoting the GDPR.

The regulation has so far prompted large fines of several high profile companies: In 2019, Google was fined 50 million Euros for failing to comply with data use and disclosure requirements. The same year, Marriott and British Airlines were fined 110 and 204 million Euros respectively, for failing to properly protect consumers from hackers. Twitter, Oracle and Salesforce may be the next to face fines for failing to comply with the law.

Ke and Sudhir’s paper challenges and nuances the view that additional regulation harms businesses by examining the long-term effects of the law through a game theoretic analysis of the market dynamics.

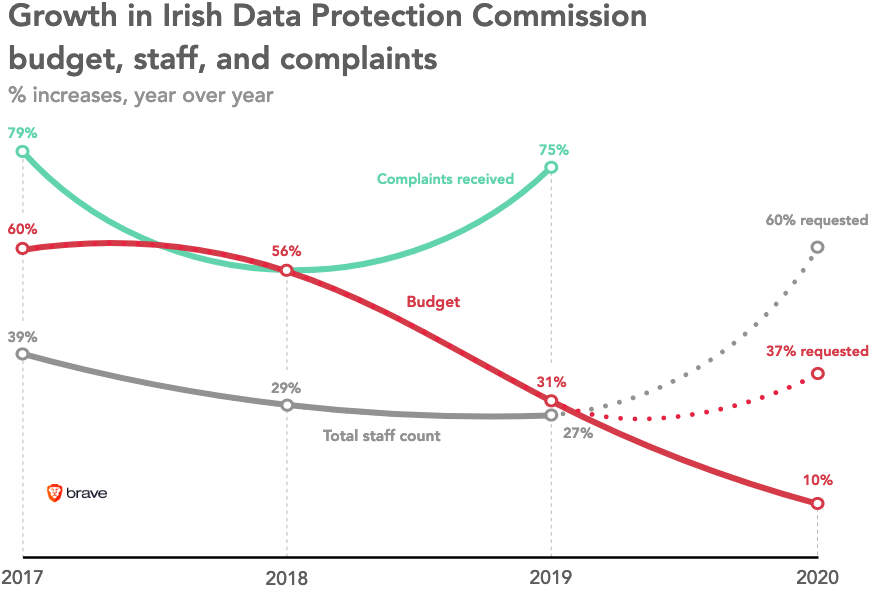

A common anti-regulatory critique is that the law is bad for firms’ bottom lines and consumer welfare by placing burdensome restrictions on data use and threatening large fines. One detractor in the Financial Times argues that requiring firms to explain how personal data was used in their machine learning models was forcing firms to jettison opaque but effective AI systems. The author also points to a troubling drop in venture capital for EU technology companies during the 12 months after the legislation was implemented: the sector saw 1/3rd less funding after the GDPR than before it. Regulators across the EU have faced critical shortages in personnel and budget as GDPR-related complaints have increased. Given the widely reported lack of public awareness of or trust in the regulation, critics of the GDPR argue the burdens on firms aren’t worth the benefits to consumers.

According to a Brave report, Ireland’s Data Protection Commission has faced critical shortages. Many EU regulators have faced the same issues.

Ke and Sudhir’s paper challenges and nuances the view that additional regulation harms businesses by examining the long-term effects of the law through a game theoretic analysis of the market dynamics. In the next sections, we discuss the metrics the paper uses to evaluate the regulation, the specifics of their model, and the results they predict.

How should we evaluate the GDPR?

Ke and Sudhir consider several questions about the effects of the GDPR for companies and consumers:

- Under what conditions does the law benefit consumers, and which customers does it benefit? Europe’s data protection authority declared the EU needed “a comprehensive approach on personal data protection” and cites the privacy component of the European Convention on Human Rights as a key raison d’etre, making consumer welfare central to the regulation. Consumer welfare can be measured using consumer surplus, or the difference between the greatest price consumers are willing to pay and the market price for a product.

- Are there circumstances where the law will increase firm profit? Are firm profit and consumer welfare at odds or can benefits for consumers lead to a concomitant increase in firm profits? Firm profits can be measured using firm surplus, or the difference between the market price and the lowest price firms would be willing to sell for.

- Will the total volume of personal data in the market under the GDPR increase or decrease? Critics argue that the opt-in requirement will throttle the amount of data available to firms.

The paper models the dynamics of firms and consumers in the personal data economy to compare the market effects of the regulation to what would have occurred without the regulation. It also seeks to explain recent empirical evidence about how the regulation is affecting the market: for example, how a European telecommunications company saw an uptick in opt-in for data collection while other firms haven’t.

A novel intertemporal model for analyzing privacy law

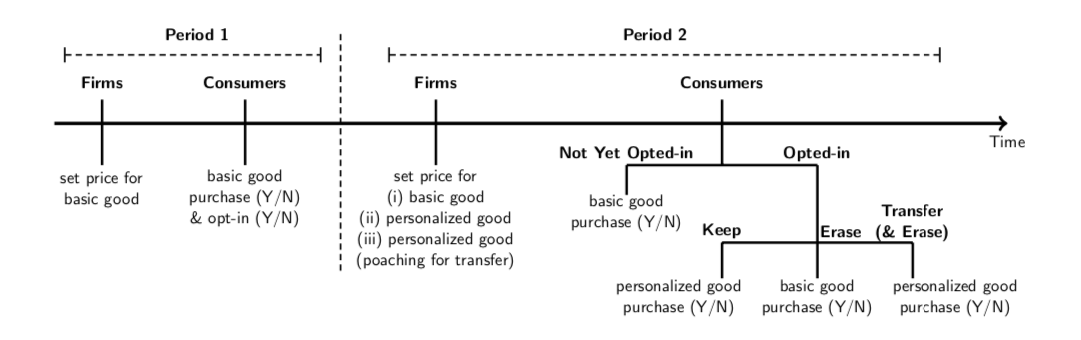

The arguably most important feature of the GDPR is the right to affirmative and on-going consent for data collection. This can be thought of as a two-phase process: consumers first either opt in or opt out of data exchange when they first buy a good or service from a firm, then they face a second decision at a later stage as to whether they should keep their data with the firm, delete it or transfer it to a competitor.

Similarly, firms make decisions about each customer in two phases: in the first phase, they determine the price they charge for the basic product, without access to the personal data of the consumer; in the second phase, if the customer provided consent for data exchange, the firm can change the basic product in a few ways:

- They can personalize the product to increase the value they provide to the consumer. For example, Spotify’s or Netflix’s algorithms might learn your tastes and improve value by making recommendations for new music or movies you might like.

- They can charge different prices for different consumers on the basis of the data. This behavior is called price discrimination, and it can increase consumer surplus for some customers and decrease it for others: retailers can offer first-time discounts or loyalty benefits; Uber can charge higher prices during times and near locations with high demand. Firms use price discrimination to maximize profits over different subsets of consumers based on their differing preferences and behavior.

The paper encodes these intertemporal choices, or multiple time-sensitive and interrelated decisions, that consumers and firms make as a two-period game. See the figure from their paper below.

Timeline of the game.

In the game, there are \(n \geq 1\) firms offering a basic product. The consumers have a valuation \(v\) of the basic product which follows a uniform distribution on the interval \([0,1]\). In the first period, if the customer opts in to data exchange, the firm can learn the customer’s valuation of their product from the data, and they can personalize the product to increase the customer’s valuation in the second period. If the customer opts into the data exchange, they are also exposed to the risk of a privacy breach, which carries with it an expected cost \(c\).

One of the key contributions of the model to the existing literature is the endogenization of personal data choices on the part of firms and consumers; the model includes these decisions as features and tries to determine how they are affected by the other parameters.

If the customer shared their personal data with the firm in the first period, they benefit from personalization of the product in the second period. To reflect the fact that different customers may value personalization more or less highly, there are two types of customers: some consumers value the personalized product at \((1 + \kappa_H) v\) and others value it at \((1 + \kappa_L) v\) where \(\kappa_H > \kappa_L > 0\). Firms are assumed not to know \(\kappa_L, \kappa_H\), while customers learn which of \(\kappa_L, \kappa_H\) is their personalization bonus if they share their data before they make their second period decision.

One of the key contributions of the model to the existing literature is the endogenization of personal data choices on the part of firms and consumers; the model includes these decisions as features and tries to determine how they are affected by the other parameters. Concretely, the model allows for consumers to decide to opt in or opt out of data sharing in the two periods and for firms to set prices. Both consumers and firms are assumed to make the choices that maximize their welfare, but since their circumstances and preferences are heterogeneous, different types of consumers or firms can make different decisions. The paper also separately analyzes the model when breach costs are exogenous (due to developments in technology out of the control of a firm) or endogenous (a result of privacy and security practices within the control of the firm). As we will see in the next sections, whether or not firms can control the cost of data breaches plays a significant role in the degree to which the GDPR is beneficial for consumer and firm surplus.

Personal data markets subject to the GDPR: what to expect

To make predictions about how the market will behave with and without data privacy regulations, Ke and Sudhir solve for equilibrium in the game described in the previous section. The strategies of customers and firms in equilibrium determine market segmentation: based on the expected costs associated with data breaches \(c\) and the personalization preferences \(\kappa_H, \kappa_L\), it is possible to see which consumers will purchase the good, whether they will share their data and how firms will set prices. The different behaviors of these segments of the population determine consumer surplus, firm surplus and the volume of data in the market. According to Ke and Sudhir’s analysis of the model, the regulation should have different effects on monopolistic markets (\(n=1\)) and competitive markets (\(n>1\)).

Consumer Surplus

Let’s consider consumer surplus under the monopolistic market first. Recall that consumer surplus is the difference between what consumers are willing to pay for a product and the market price.

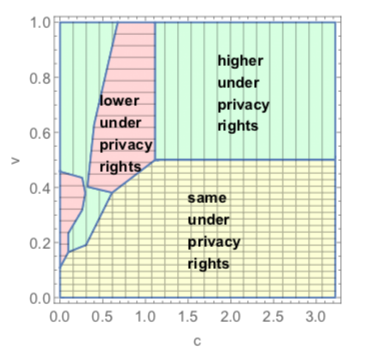

Consumer surplus depends on consumers’ valuations and privacy breach costs. We can break down the interacting effects of these two variables using the following chart from the paper.

A plot from the paper showing the benefits of privacy rights by consumer valuation for a certain parameter setting.

On the vertical axis is the customer valuation, \(v\). On the horizontal axis is the privacy breach cost, \(c\). Customers with low valuations of the product, \(v < 0.5\) will not buy the product at all in either case, so the privacy regulation won’t make a difference for them (yellow region).

Things get more complicated for the top half of the graph (green and red regions), the region corresponding to high-valuation consumers. Under the GDPR, consumers can always stop sharing their data and switch to a basic product if they are being charged an unfavorable price for the personalized product. This limits the ability of firms to price discriminate. This has different effects depending on whether breach costs are low, medium or high. If breach costs are low, customers risk very little by sharing their data and benefit from protections against price discrimination under privacy rights. So these consumers are better off under the GDPR (green region on the top left). If breach costs are high, firms are willing to subsidize the price of the personalized good to encourage consumers to share data (green region on the top right). However, if breach costs are at an intermediate level, customers are averse to sharing their data because of the breach costs and companies are not willing to subsidize the price of the basic good. So consumers are better off without privacy rights for intermediate values of \(c\) (red region in the top center). For more details, see section 3 of the paper.

Under the GDPR, consumers can always stop sharing their data and switch to a basic product if they are subject to unfavorable prices for the personalized product. This limits the ability of firms to price discriminate.

Competitive markets (\(n > 1\)), according to Ke and Sudhir’s analysis, are likely going to see greater benefits for consumers under the GDPR than monopolistic markets. In a competitive market, competition drives down the price for the basic product down, and the ability for firms to price discriminate is even more weakened. This is because customers can transfer their data to a competitor that has more favorable prices and similar personalization value. Thus, privacy rights should lead to higher consumer surplus for all customers at all breach costs \(c\).

Firm Surplus and volume of data

In monopolistic markets, firms should see higher profits when breach costs are high. This is because the data privacy regulation allows consumers to purchase goods without sharing high-risk data — there should be increased exchange of goods without exchange of data. When breach costs are low, firms should see decreased profits, since the regulation limits their ability to price discriminate.

In competitive markets, firm profits should be lower under the GDPR relative to without the GDPR for most privacy breach costs \(c\). This is because fewer consumers will share their data, and competition drives prices down. However, when privacy break costs are high, firm profits may increase for the same reason as in the monopolistic markets: more consumers will purchase the product without sharing their data. Across the board, the GDPR should hurt firms in competitive markets more than those in monopolistic ones.

For both monopolistic and competitive markets, the GDPR should weakly reduce the volume of data in the market.

Privacy breach costs: endogenous or exogenous?

Ke and Suhir also address how choosing whether data breaches are endogenous or exogenous features of the model can change the dominant effects of the GDPR on consumer welfare and firm profits. In the analysis above, they assume that privacy breach costs are exogenous to firms; the firms each have the same privacy breach costs, which are a result of technological factors primarily outside of their control as long as the firms meet baseline GDPR security requirements. However, when privacy breach costs are endogenous, firms can invest in their own security in order to reduce expected privacy breach costs. The market equilibrium changes: Ke and Sudhir find small increases in firm profits, consumer surplus and the volume of data in the market when breach costs are endogenous relative to when they are exogenous.

Takeaways

Ke and Sudhir’s analysis of personal data driven market dynamics gives us a sense of the dominant trends to expect in the GDPR in the EU:

- In a given market, the total volume of data available to firms could go up or down depending on privacy breach costs and benefits from personalization for consumers, since privacy rights should reduce opt-in and increased security should increase opt-in; however, even when the volume of personal data is lower, markets may benefit from greater consumer spending — consumers have greater flexibility to separate the exchange of goods and the exchange of data.

- Consumer surplus should always go up in competitive markets and usually go up in monopolistic markets as a result of the increased flexibility of the law. Consumers with high valuations of a product will benefit more than consumers with lower valuations.

- Since price discrimination and the threat of data transfer hurt firms more in competitive markets than monopolistic ones, the GDPR will hurt firms in competitive markets more than those in monopolistic markets.

- When firms can lower data breach costs by investing in better security, we should see consumer and firm surplus increase, regardless of the privacy and security regulations in place.

For consumers, the findings suggest that the GDPR will not only lead to more transparency in the flow of personal data, but also increase surplus by disincentivising price discrimination and encouraging firms to create value for customers through personalization.

Firms may be able to discern from the analysis the relative benefits of investing in greater security depending on the circumstances of their market. They may also be able to predict the market segmentation that could occur under the data protection regime.

For consumers, the findings suggest that the GDPR will not only lead to more transparency in the flow of personal data, but also increase surplus by disincentivising price discrimination and encouraging firms to create value for customers through personalization.

Regulators around the world considering similar privacy legislation should also take note of the heterogeneous effects on markets as a result of the GDPR: depending on their circumstances, firms may see either an increase or decrease in data flow and/or profits depending on their ability to reduce breach costs.

Since Ke and Sudhir’s analysis captures the intertemporal decisions that consumers and firms make with and without privacy legislation, their model would be interesting to apply to other personal data protection regimes worldwide. One limitation of their work, however, is that the analysis does not account for the dynamics of third-party data markets, the ecosystem of contractors, advertisers and cloud-service providers buying, collecting, processing and selling data on behalf of other firms. Firms and consumers in third-party data markets may see different outcomes when the flow of personal data between firms is regulated. Future empirical research may be able to verify the dynamics of the market as the GDPR regime matures, while future theoretical analysis may be able to explore the effects of third-party data markets and privacy regulation in other parts of the world.